Sometimes you do your best to get your web application ready in time and you actually do, but then you are challenged by its performance. It works, but it takes time to respond, it challenges the user’s patience, meaning, that’s a problem you need to take care of. The question is, how do you get around that?

There are different techniques that help us get around this and I’m writing this article to share my experience with the few I know and have tried, but, before we dive into the techniques pool, Let me state that this article is not meant to be the “definitive guide of web applications navigation speed optimizations” and it doesn’t also cover back-end specific optimization techniques.

Shall we begin?

Http Resources caching

The web sits on top of the HTTP protocol. The HTTP protocol is Request-Response based, where Requests and Responses have headers and content. Headers are used to pass meta-data and trigger certain behaviour, both on the server and client-side. So headers present in a Http request are read and interpreted by the server and headers present in a Http response are read and interpreted by the client. There is something very peculiar to be told about Http headers, is that, they must be sent before the content. Why? because as we said before they serve as some sort of meta-data or behaviour triggers regarding the HTTP content.

HTTP Caching is implemented via HTTP headers. We basically add a few headers to the HTTP Response and tell the browser that it must cache the HTTP Response for a specific period.

The thing about the HTTP caching is that it caches data on the client-side (a browser most of the times) and it does require the client to make contact to the server in the first time, so it improves further requests, the initial load requests still not optimized by this technique. There is another peculiarity regarding this method: how do you update content that was cached on the client-side?

Versioned resources

Let me describe the problem once again so that I can be sure we are both in the same boat: we want the client to cache content and avoid trips (requests) to the server, but at the same time, we want to have control over that same cached content. What do I mean by “control”? I mean: How do we update the cached content? Lets first dive into “how the whole caching thing works”. The client makes an initial GET request to the server and the server replies with the page content. The page content has references to other resources like scripts, style sheets and images. So, the client makes another GET requests in order to retrieve the referenced resources and that’s where the caching kicks in: before the client contact the server to retrieve the resource, it checks if the resource is not cached. This verification is based on the resource’s path. The path is our key to control the content cached on the client side. We just need to use a dynamic path. Because, once we change the path, even if it’s a minimum difference, the client will have to contact the server and retrieve the last version of the resource. You don’t need to be renaming the resource file. You can make the URL dynamic by adding a prefix or suffix to it and making such suffix change on each build of your application. I’m sure webpack can help you on this.

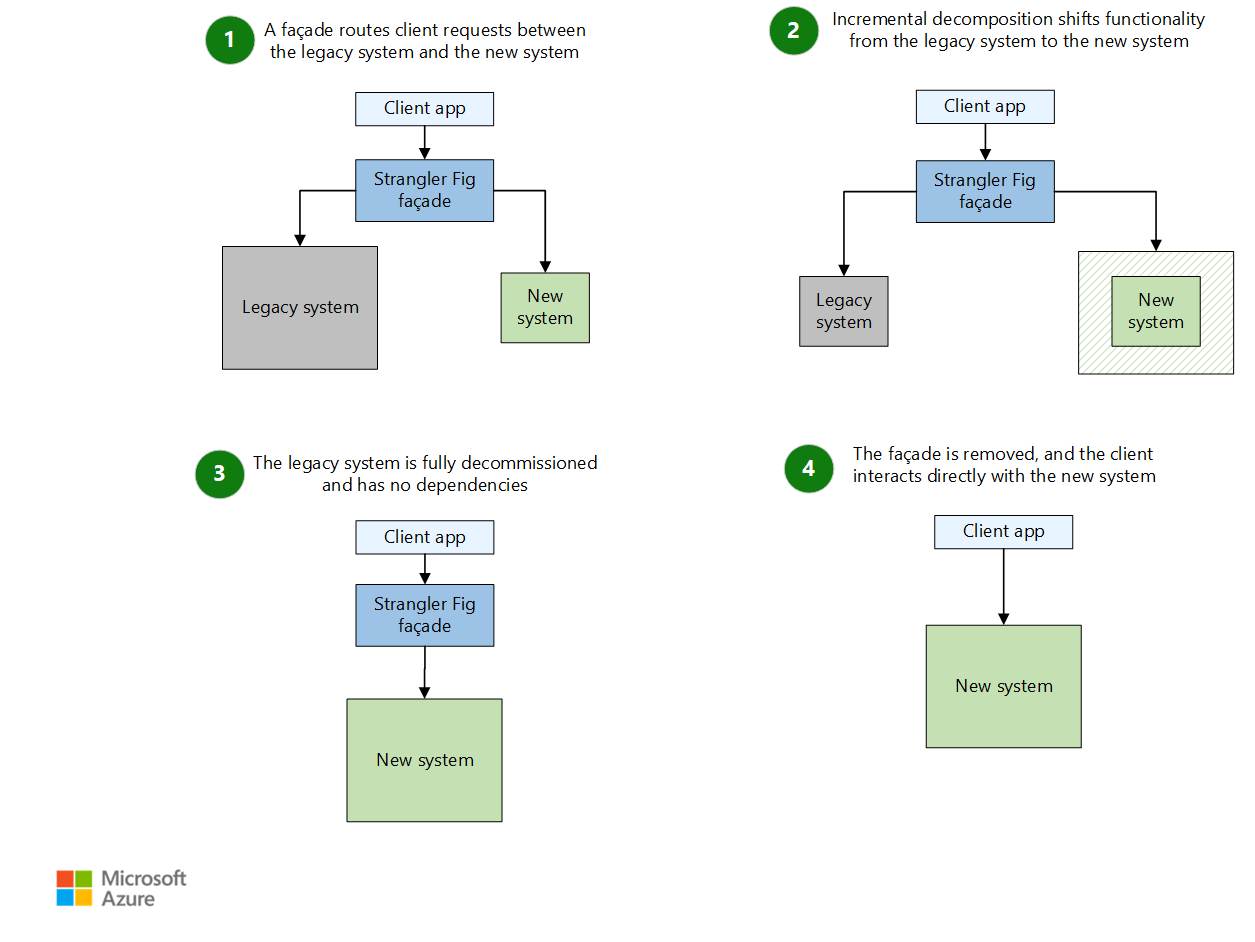

Server output caching

Web applications are pages with dynamic content, in other words: dynamically generated HTML. There currently two approaches to build web pages with dynamic content. Or we trust the browser (a JavaScript enabled one) to make the content dynamic by simply going to the server to fetch JSON data then perform DOM manipulation using JavaScript – a.k.a AJAX OOOOR we can go Naïve and let the server provide the full HTML . This technique is best suited to situations where full HTML is Being fetched from sever. But why? Because it has more enhancement impact in such situations. HTML is a lot more verbose than JSON, plus, generating HTML on the server side will likely involve a trip to a data source plus template engine processing, which means fetching JSON is in theory faster than fetching full HTML. Server output caching is to store the HTML generated by the server on a caching storage so that the it can be served the next time the page is requested. Let’s make a little sketch on this:

Seems awesome right? But there is a non answered question yet: when is the cache going to be updated? Adding an output caching layer creates the possibility of displaying out of date content to users.

Cache invalidation

The path to find the right cache invalidation approach is to ask yourself the following question: Where is the data that is making your HTML dynamic, coming from? Most of the times, the answer for this question will be: a database. But it doesn’t matter the answer. The point is that you must invalidate a cached page when the data that was used to generate that page is updated. When I say “when the data is updated”, I mean it. It has to be right on the moment if you don’t want to be serving pages with out of dated content. You will need some messaging or event system to address this. You will end up with a design like this one:

Resources Minification

This one sits on top of basic concept: The smaller the data you ship from the server to the client, the faster the page load gets. Minification consists of reducing size of stylesheets and scripts by removing spaces, line breaks and performing some additional processing to put the file as small as possible. Nowadays, you don’t need to minify your assets outside of your project, you can integrate a minifier directly in your build process. Ask WebPack and Maven about it. These are just examples, of course. The caveat of minification is code readability when debugging the web application in production, it will drive you crazy.

Load assets from CDN

CDN stands for: Content download network. What is to load an asset from a CDN? Why load assets from CDN? Where else would the assets be loaded from? A CDN is responsible for caching web content and serve it from the server that is closer to the user requesting the content. CDNs are prepared to handle a high load of requests, meaning, you can rely on them. You may load libraries like jquery, angular and others from a CDN and be sure that it will get loaded as fast as possible. On the other hand, you don’t have to download the libraries into your web applications directory structure. You are simply pointing to a web content using a URL. Take Facebook as an example: they use their own CDN to load photos (https://fbcdn.net ) you can check it yourself by inspecting the facebook web app.

The caveat of this method is: potential incompatibility with production environment policies. Sometimes you a web app that is being server in a VPN with very strict firewall rules and users aren’t allowed to fetch content from external servers (Internet).

Stylesheets and script Concatenation (webpack)

You might be tempted to believe this is the same with Minification but it’s not. Concatenation is the act of joining multiple files into one. What are the advantages of this? When you have multiple resources to load, you have multiple requests to be fired and you will have the DNS lookup overhead for each of the requests and then you also have the connection establishment overhead (although keep-alive can minimize this one) and the number of resources to be simultaneously loaded from the same domain is limited and varies from browser to browser. Instead of having the browser trying to fetch for example jquery and bootstrap in separated request, why not concatenate them into one single file (during the build process would be the right moment). Webpack is very good to setup a concatenation pipeline, and it’s simple to use (right now I sound like some Webpack activist). The caveat of the concatenation is the possibility of loading content that the current user won’t even be accessing: JavaScript based applications are the most vulnerable to this, but fortunately it’s an issue that developers can easily get around. Concatenate the right assets and you will get performance improvement, concatenate the wrong ones and you will damage the user experience.

Multiple domain names for faster assets loading

Each Browser defines a maximum number of requests to be done concurrently to the same domain name.

This limit affects your web application performance obviously and if you are sure that you will need to concurrently load more content than most of the browsers allow you, then, it’s time for you to create multiple sub-domains for you web application and use each of the sub-domains to load a specific set or type of content. For example, in Youtube, the images that we see as video thumbnails, are being fetched from a different domain which is https://ytimg.com. You can see it by yourself, by simply inspecting the youtube website. Facebook also uses the same technique (photos CDN, remember?), LinkedIn and Twitter all embrace this technique because it really makes the difference. Remember that each browser imposes its own limit, and if I were you, I would work based in the lowest limit because pre-processing the content differently to each of the browsers will also bring some overhead and may even kill the optimization you will be trying to get. This technique requires you to pay some attention regarding the cookies. Make sure they point to the domain an not to a specific sub domain, unless you know what you are doing.

GZIP compression

This optimization is the cheaper one, because nowadays, most of the web servers offer some config way to get the GZIP compression in place. But wait? What is GZIP Compression? It’s a data compression algorithm. Would it require you to include some lib into your web application? No. The content compression should be handled in the infrastructure level because it’s directly related to the communication protocol, which is HTTP. The thing about data compression on the web, is that the server can only compress data in a format the client can decompress, so, the client must tell the server which compression formats it supports. This is done via HTTP request headers, to be more specific, The Accept-Encoding header. The server then decides which compression algorithm to use, among the ones the browser supports . The server must say which compression algorithm it used to compress the web content, meaning it must also Cary an http header, which is: Transfer-Enconding. The most supported compression algorithm is GZIP and you can safely encode your web content using this one, because every modern browser will be able to decode the content (as long the Transfer-Encoding header is there with the correct value). Employing a compression algorithm requires you to know which browsers support such a algorithm and analyze if your audience is using such browsers, because using a compression algorithm that is only going to be supported by 2% of your audience will not improve the overall user experience, unless you have the power or possibility to force your users to use a specific browser without going against an internal policy and or without degrading the user experience in other aspects. When I say other aspects, I mean this: the browser might support an encoding format the others don’t, but it might not support some HTML5 feature (eg: server-sent events) that your application relies on, or it allows a smaller number of simultaneous requests than any other. These are the “other aspects” I’m talking about and you better not limit yourself to these. Enough of Gzip.

Images resize

This one is classic and simple. Why do you need a 1024×800 image if you always display it as a 32×32 icon? Just resize the image to the size you are actually displaying it. The problem with using a huge image and then resize it to a fixed dimension is to be downloading a relatively huge file when there is no need. Just resize and compress, there a countless online compressors. Go and find yourself one and STOP having huge images that are resized by the browser. Users will thank you because the page loads faster and the page will also consume less data.

Trade images by CSS

We are no longer in a era that demands images and JavaScript to provide some basic animation on web-pages, we are now in the CSS3 era and we got resources to push out most of our image based effects and re-create them with CSS. The rendering performance will be superior and loading performance also will, because there is no “quality loss concept” in css. You can minify the css and you can also concatenate your stylesheets to improve the website’s download time, while this is something that requires more effort with images: image maps, I never liked them but they aren’t always the wrong choice, it’s just that most of times they are.

Asynchronous script loading : lazy-loading

All Ajax applications rely on JavaScript to reach out the server and then fetch some data, Being it JSON or not. The point here is that, most the times the user is not interacting directly with the server, his actions are being responded by JavaScript which decides wether to contact the server or not. The idea of asynchronous script loading is: only load the script when you know the user will interact with it. By doing this you get a lower initial load duration, on the other hand, the user will have to wait for the script to be downloaded when he attempts to trigger it for the first time. This technique will simply distribute the download time between the initial download and the subsequent downloads. The web application may even get slower (the overall download time increases) because of the multiple DNS lookups but the user will be satisfied for sure, because he won’t have to wait longer because of scripts he won’t even trigger.

Server-side rendering (with Virtual DOM)

We have all heard rumors about the miracles that the big JavaScript players like ReactJS, VueJs and Angular2 can do in terms of performance improvement. These frameworks shine because of a particular characteristic: the server-side rendering. Server-side rendering consists of executing JavaScript on the server-side, generating DOM to be sent to the browser and then immediately rendered. These frameworks are based in a concept named Virtual-DOM and they implement this concept In a way that DOM can be generated and manipulated in a headless javascript environment like NodeJS. Do we really get some improvement by rendering dynamic content on the server-side? How? I Personally only look the server side rendering as an initial load improvement tool. But How does it improve the load time?

The client issues a request to the server and then the server processes the request executing the JavaScript that generates virtual DOM trees and then the virtual DOM trees are converted into actual DOM trees (HTML) which is then handed to the client in a HTTP Response so that the client can render it immediately.

The assumption here is that, running JavaScript on the server-side is faster than running it on the client-side and this is most of the times true, because being it true or not, you do have control over the server-side and you can still improve the JavaScript execution performance by scaling your server-side rendering infrastructure.

Server-side rendering gives you the possibility to scale JavaScript (that manipulates DOM) that was supposed to run on the client (browser).What about the Virtual-DOM? First of all, Virtual-DOM abstracts the actual DOM. It shines on the diff and merging algorithms.

When for example, we want to modify all the elements with a specific css class. The Virtual-DOM, will perform this action on its virtual DOM tree and then will find the differences between the virtual DOM tree and the actual DOM tree and then merge the differences. This process is guaranteed to me much faster then performing the action directly on the actual DOM tree. Need details? Go find yourself some Virtual-DOM tutorial, this is not one! Lets move to the next and last optimization technique.

Keep connection alive

Web servers and web clients communicate using TCP connections. By default (HTTP versions prior to 1.1), one HTTP Requests stands for one TCP Connection. This optimization consists of using the one TCP connection for multiple HTTP Requests, avoiding the overhead that each connection establishment is subjected to. This is the default behaviour regarding TCP connection since HTTP 1.1. Make sure your clients and your server both support Http connection persistence.

Thank you for joining me. Please share your experience.

Its always a pleasure!

Comentários Recentes